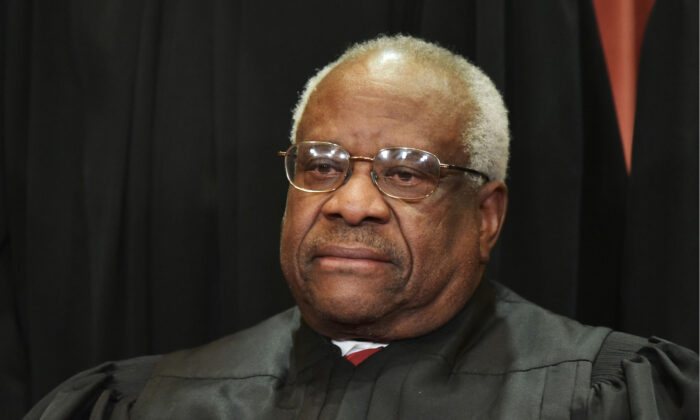

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas poses for the official group photo at the U.S. Supreme Court in the District of Columbia on Nov. 30, 2018. (Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images) Constitutional Rights

By Jack Phillips April 5, 2021 Updated: April 5, 2021 biggersmallerPrint

Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas appeared to signal that Big Tech firms could be regulated after Facebook and Twitter suspended President Donald Trump earlier this year.

Thomas, considered a conservative on the high court, made the point during a 12-page submission as the Supreme Court issued an order that rejected a lawsuit over Trump’s blocking of certain Twitter users from commenting on his posts before his account was taken down. The Supreme Court said the lawsuit ultimately should be dismissed as Trump isn’t in office anymore and was blocked from using Twitter, coming after the Second Circuit Court of Appeals had ruled against Trump.

“Today’s digital platforms provide avenues for historically unprecedented amounts of speech, including speech by government actors. Also unprecedented, however, is control of so much speech in the hands of a few private parties,” Thomas wrote Monday (pdf). “We will soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.”

Thomas also noted there are arguments suggesting digital platforms such as Twitter or Facebook “are sufficiently akin to common carriers or places of accommodation to be regulated in this manner.”

Thomas made reference to the respective owners of Facebook and Google by name—Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Page, and Sergey Brin.

“Although both companies are public, one person controls Facebook (Mark Zuckerberg), and just two control Google (Larry Page and Sergey Brin),” he wrote.

Thomas agreed that Trump’s Twitter account did “resemble a constitutionally protected public forum” in certain aspects, he noted that “it seems rather odd to say that something is a government forum when a private company has unrestricted authority to do away with it,” possibly referring to Twitter’s ban against Trump following the Jan. 6 incident.

“Any control Mr. Trump exercised over the account greatly paled in comparison to Twitter’s authority, dictated in its terms of service, to remove the account ‘at any time for any or no reason,’” he added. “Twitter exercised its authority to do exactly that.”

Thomas then said that modern technology isn’t easily addressed by existing laws and regulations. But he warned that the Supreme Court may “soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.”

“The Second Circuit feared that then-President Trump cut off speech by using the features that Twitter made available to him,” Thomas said. “But if the aim is to ensure that speech is not smothered, then the more glaring concern must perforce be the dominant digital platforms themselves. As Twitter made clear, the right to cut off speech lies most powerfully in the hands of private digital platforms. The extent to which that power matters for purposes of the First Amendment and the extent to which that power could lawfully be modified raise interesting and important questions.”

Thomas noted that Big Tech firms have a vast amount of power over the flow of information—even books. He said it does not matter that Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, and others are not the only ways in which to distribute speech as long as their power to do so is unequaled.

“A person always could choose to avoid the toll bridge or train and instead swim the Charles River or hike the Oregon Trail,” he wrote. “But in assessing whether a company exercises substantial market power, what matters is whether the alternatives are comparable. For many of today’s digital platforms, nothing is.”